The Science of Climate Change

The world is warming

Our climate is changing in many ways. One of the clearest signs is that the world is warming. Scientists know this through evidence compiled from satellites, weather balloons, thermometers, weather stations and more.1 Since 1880, average global temperatures have increased by about 1 degrees Celsius (1.7° degrees Fahrenheit). Global temperature is projected to warm by about 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7° degrees Fahrenheit) by 2050 and 2-4 degrees Celsius (3.6-7.2 degrees Fahrenheit) by 2100.2

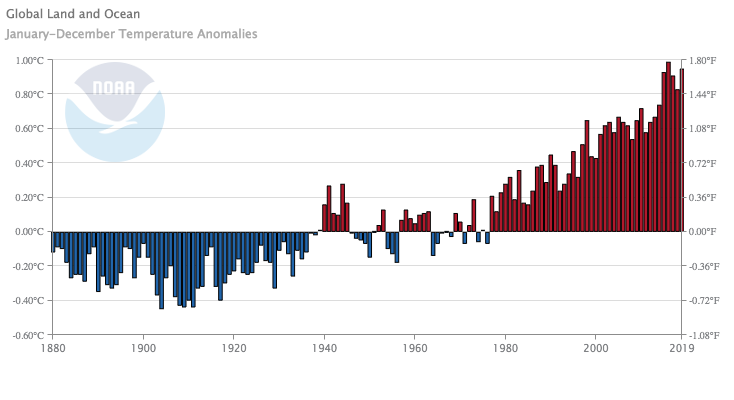

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), average annual global temperatures have increased steadily since the 1960s. Figure 1 shows deviations from the average global temperature depicted as the horizontal line at 0.00 degrees Celsius. Every blue bar is a year that was colder than the average temperature of the 20th century. Red bars are years that were warmer than the 20th century average. Nineteen of the 20 warmest years have occurred since 2001. It is likely that the coldest year moving forward will be warmer than the warmest year that we experienced in the 20th century.

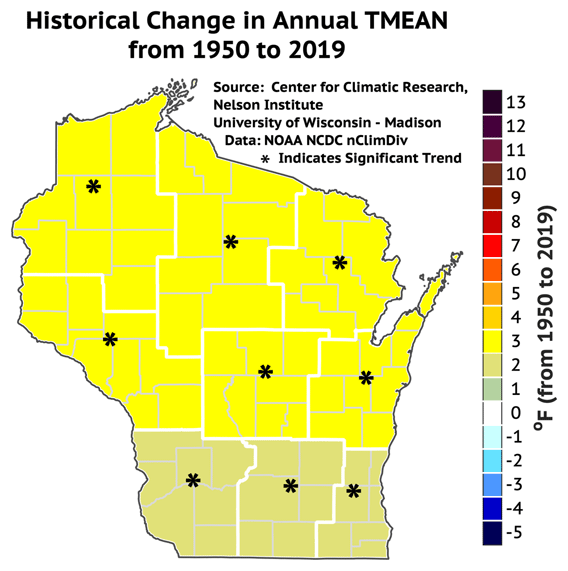

To determine changes in Wisconsin temperature and precipitation, scientists from the University of Wisconsin-Madison analyzed temperature records from a statewide network compiled by the National Climatic Data Center. This dataset shows that Wisconsin has become 2 degrees Fahrenheit warmer and 4.5 inches (14 percent) wetter since the 1950s, with the greatest warming during winter and the largest precipitation increase during summer (Figure 2).

Carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere are increasing

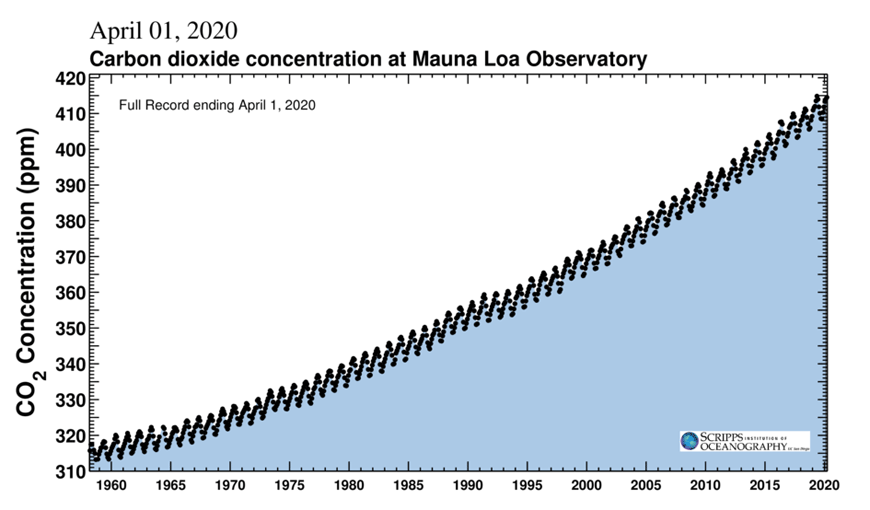

Recordings of daily atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2), initiated by Dr. Charles David Keeling of the Scripps Institute of Oceanography, help to tell the story of increasing CO2 levels. Keeling was curious whether the increasing amounts of fossil fuel being combusted would affect atmospheric CO2 levels. So, in 1958 he began to record daily atmospheric CO2 levels at the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii. Mauna Loa was selected as a long-term monitoring site because it was far from other continents and vegetation that could affect the CO2 concentration. The daily recordings are considered one of the world’s greatest scientific contributions.

Keeling's measurements discovered an annual planetary cycle in CO2 , in which CO2 levels rise and fall seasonally (Figure 3). This cycle is tied to photosynthesis. In the spring as plants grow, they take carbon dioxide from the air and using the energy from sunlight, convert it into carbon and release oxygen. In the fall as plants die, they release CO2 and global CO2 readings rise.

In addition to the seasonal cycling, Keeling also recorded an increase in CO2 concentration over time, from 313 parts per million (ppm) in 1958 to 415 ppm as of March 30, 2020. This rise in CO2 concentration, known as the Keeling Curve has transformed the way scientists understand the source of CO2

Increasing carbon dioxide is due to human activity

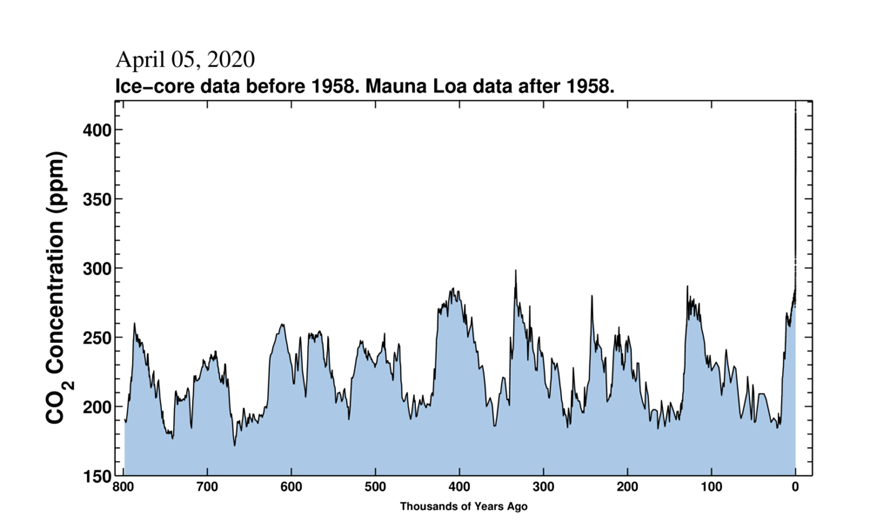

Scientists understand the source of CO2 in the atmosphere from several lines of evidence, including measurements of Antarctic ice cores that go back 800,000 years. Antarctic ice cores contain our atmosphere’s history in bubbles of air that were trapped hundreds of thousands of years ago when the ice was first formed. Scientists can analyze these bubbles to determine how CO2 levels have changed over time.3 The cores show that for the last 800,000 years, until about 1900, CO2 levels were relatively stable, fluctuating between about 150 and 280 ppm. In the early 1900s, CO2 started to increase at an unprecedented rate. Today, only 120 years later, CO2 levels are 40 percent higher than they were before the industrial revolution (Figure 4).

CO2 emissions make up the vast majority of greenhouse gases (GHG) that warm the planet. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Air Management Program has prepared the Wisconsin Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventory (1990-2021), identifying CO2 and other GHG emissions in Wisconsin for 2005 and 2021, and describing emission trends from 1990 through 2021. Report authors used the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s State Inventory Tool populated with default data.

Downscaling Data to Predict Future Trends: What climate change means for Wisconsin

Research conducted by the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts (WICCI), a collaboration of more than 200 scientists and practitioners, provides useful information on the impacts of climate changes, adaptive strategies and solutions to both store carbon and reduce carbon emissions. The University of Wisconsin-Madison's Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources lead WICCI.

WICCI climate scientists have been able to project local temperature and precipitation patterns for Wisconsin. The scientists took taking global climate models that simulate climate changes on a large scale (typically 100-200 miles) and downscaled them to approximately six miles. The downscaled models have allowed scientists to forecast more realistic, localized temperature and precipitation changes, and changes in extreme weather events. WICCI scientists are continuing to work with people around the state to fine-tune these models and provide forecasts for other climate factors that are important to impacts in Wisconsin.

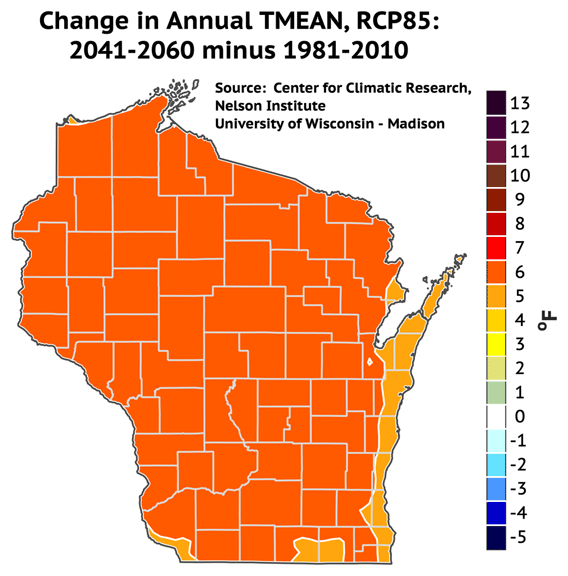

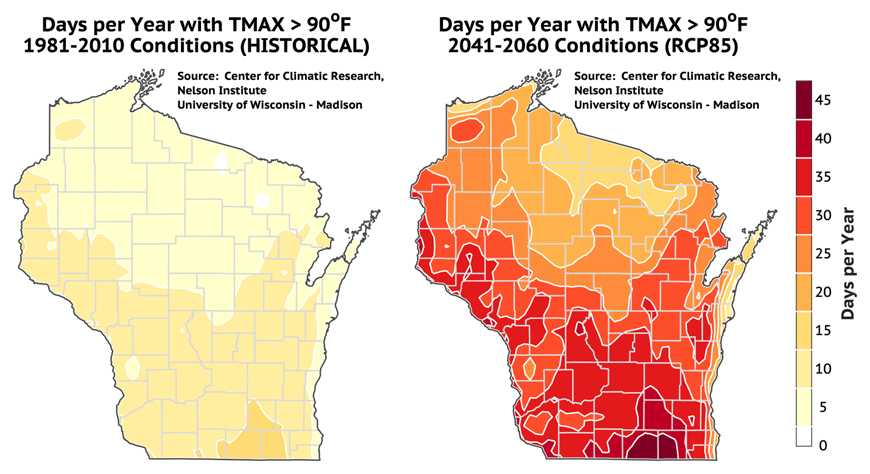

Temperature

Wisconsin is likely to become a much warmer state over the next few decades, with average temperatures closer to southern Illinois or Missouri. Results show that Wisconsin has warmed 2 to 3 degrees Fahrenheit since 1950, and it is projected that the state will warm an additional 2 to 8 degrees by 2050 (Figure 5). We will also likely see a tripling in the frequency of extreme heat (days above 90 degrees Fahrenheit), rising from about 10 days per year in 2020 to about 30 days per year by 2050 (Figure 6).

Seasonal temperatures have also changed. Spring temperatures have increased by 1.7 degrees Fahrenheit with the onset of spring (defined as the date when daily temperatures have reached 50 degrees Fahrenheit for 10 days in a row) coming three to 10 days earlier since 1950. Wisconsin winters are becoming less cold and have warmed more than any other season in recent decades, especially in the northwestern part of the state where average temperatures have increased by as much as 4.5 degrees Fahrenheit. It is anticipated that winter temperatures will continue to increase 5 to 11 degrees Fahrenheit by 2050 meaning winters will be milder, about one month shorter than they are today, and will produce about 14" fewer inches of snow.

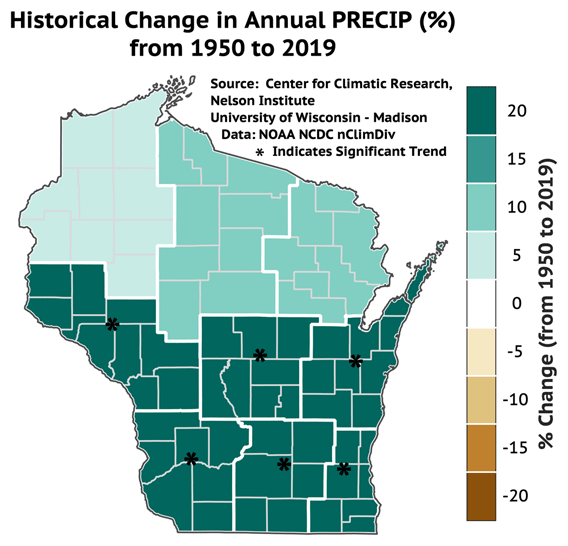

Precipitation

Wisconsin has become about 10 to 20 percent wetter since 1950. However, the increase is not evenly distributed geographically. Southern and central Wisconsin have experienced about 20 percent more precipitation than the annual average, while northern Wisconsin has not experienced a significant change in annual precipitation (Figure 7). Although projections of precipitation are less certain than projections of temperature, scientists report that annual average precipitation will likely increase by 2050, especially during fall, winter and spring. Further, in winter we are likely to see more precipitation as rain rather than snow.

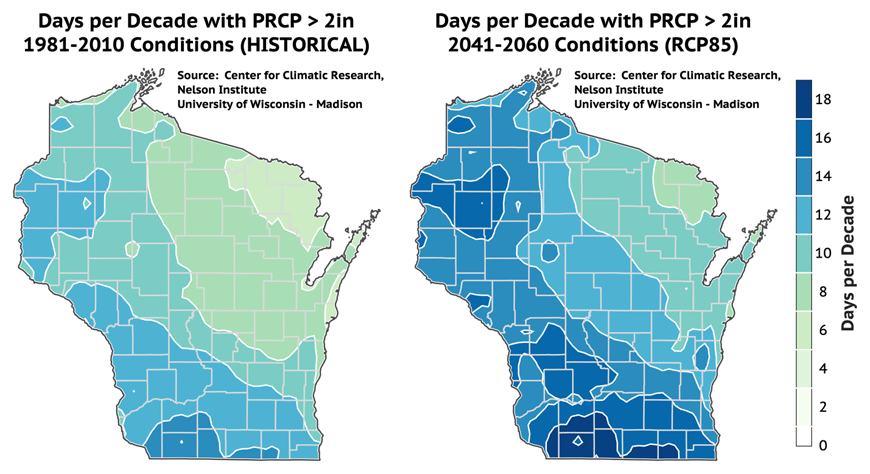

In addition to tracking average precipitation, WICCI scientists project the frequency and intensity of storms. Extreme precipitation events have had devastating consequences in Wisconsin, and they have been increasing across the state. In the Great Lakes region, rainfall in the heaviest 1 percent of rain events increased by 31 percent between 1958 and 2007.4 These kinds of extreme events are likely to become more frequent, and more severe as our climate changes. WICCI projections suggest a 30 percent increase in the frequency of 2 inch rainfall events, and a near doubling of 5 inch rainfall events (Figure 8).

Health impacts and Community Resilience

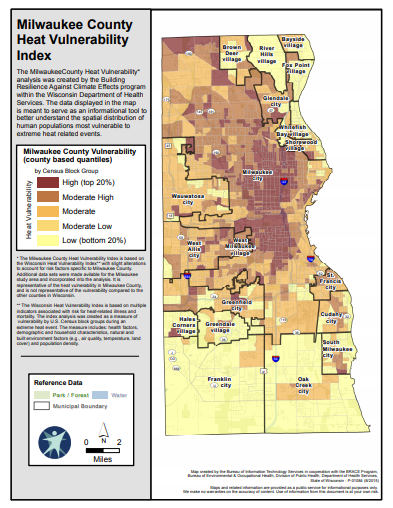

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services considers climate change such as increasing temperature, humidity, precipitation and extreme weather – one of the top public health threats of our time. Extreme heat kills more people in the U.S. than any other weather-related disaster and can disproportionately affect vulnerable populations such as elderly, socially isolated people and those with chronic health conditions such as cardiovascular disease.5,6

Heavy rains and flooding can overwhelm sewer and stormwater systems and increase polluted runoff to lakes and streams. Changes in temperature and precipitation can also impact disease-carrying insects such as ticks and mosquitos. Wisconsin's reported incidence of Lyme disease, a disease transmitted by ticks, is among the highest in the country. The rate of disease has doubled in the past decade.7

Many studies have shown that the negative health impacts of climate change are not equally distributed. Structural racism has historically been a large factor in determining what communities are most negatively impacted by environmental health issues including climate change. For example, people of color and low-income communities are exposed to air pollution and extreme heat at higher rates. Air pollution, when combined with extreme heat caused by climate change, contributes to disproportionate rates of asthma in people of color and low-income communities.

In a study of 108 U.S. cities, researchers found that when a heatwave impacts a city, poorer neighborhoods are hotter by an average of 5 degrees, but some neighborhoods are hotter by nearly 13 degrees8. Lower-income urban areas typically have more paved surfaces and fewer shade trees, parks, and green spaces, and residents typically have less access to air conditioning, increasing the risk of heatstroke. A 2020 study of 115 cities by the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Medical College of Wisconsin found lower tree canopy and higher air pollution in the poorest neighborhoods.9

1https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-global-temperature

2 Chapter 12 of the IPCC: Collins, M., R. Knutti, J. Arblaster, J.-L. Dufresne, T. Fichefet, P. Friedlingstein, X. Gao, W.J. Gutowski, T. Johns, G. Krinner, M. Shongwe, C. Tebaldi, A.J. Weaver and M. Wehner, 2013: Long-term Climate Change: Projections, Commitments and Irreversibility. In: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, T.F., D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/

3https://www.bas.ac.uk/data/our-data/publication/ice-cores-and-climate-change/

4https://www.northland.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/CRC-ClimateChangeAdaptationGuide.pdf See page 32.

5https://www.ready.gov/heat

6https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/climate/wihvi.htm

7https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/tick/lyme-about.htm

8https://www.mdpi.com/2225-1154/8/1/12/htm

9https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31884239