‘Wonderful marriage of science and art’

Colorful new harbor maps chart Milwaukee’s underwater world

IN THIS ISSUE: Expanded fishing coverage

- It's reel time

- On fishing and outdoor experiences

- Tommy White: Dean of urban angling

- Wonderful marriage of science and art

- Gear up to go fish [PDF]

- Game fish of Wisconsin poster [PDF]

Laura Otto

TROYE FOXUW-Milwaukee faculty Kim Beckmann, left, and John Janssen stand near one of the new Milwaukee fish habitat maps they helped to create.

TROYE FOXUW-Milwaukee faculty Kim Beckmann, left, and John Janssen stand near one of the new Milwaukee fish habitat maps they helped to create.Four years in the making, a unique set of maps that show what lies under the water’s surface in the Milwaukee harbor is now available both online and on signage posted at two outdoor locations near the shore.

The maps are guiding current restoration efforts that could help get the city’s harbor removed from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s list of “areas of concern,” and stimulate the local economy.

Creators of the maps, researchers from UW-Milwaukee, also say the project serves as a model for developing a tool to help improve the health of other urban harbors and estuaries.

The idea for a harbor habitat survey was born when the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources sought information that would help make a harbor degraded by urban development more attractive for fishing and recreation.

Multiple state agencies, nonprofit groups and federal entities also were interested in such mapping for different reasons — including to help them make decisions about what projects to undertake in the area.

In 2016, John Janssen, a fisheries biologist and professor in UWM’s School of Freshwater Sciences, and his then-graduate student Brennan Dow received funding from the Fund for Lake Michigan and the DNR.

Janssen and Dow, who now works full-time for the DNR, combined side-scan sonar, a method of gathering information about the depth and physical composition of the waterbed, with diving to identify the locations and activities of fish populations.

Kim Beckmann, associate professor of design and visual communication at UWM, translated the data collected into visually appealing maps with brilliant illustrations and easily digestible text so the information could be shared with the public.

BRENNAN DOWResearch by Brennan Dow has revealed plenty of fish beneath the surface in Milwaukee's rivers and harbors.

BRENNAN DOWResearch by Brennan Dow has revealed plenty of fish beneath the surface in Milwaukee's rivers and harbors.LINKING ‘FISH TANK’ HABITATS

The scientists’ data showed that more of the underwater landscape is fish-friendly than they thought it would be, Janssen said, but the areas fish use for spawning, hiding from predators and feeding were spread out and isolated.

Expanding and connecting these areas can better sustain fish populations, so Janssen and Dow also compiled a list of suggested projects to accomplish that objective.

“Think of it like it’s a fish tank,” said Dow, who is now the Milwaukee Estuary Area of Concern coordinator for the DNR. “The capacity of the Summerfest Lagoon is good, but the issue is there isn’t the right amount of habitat to support all those fish.”

An example, he said, involves linking one hotspot, where bass are spawning in the Summerfest Lagoon, to another hotspot across the harbor at the breakwall, where an abundance of tiny invasive shrimp could provide food for baby fish.

Bridging the two spots can be done by adding physical structures, such as rocks, gravel and vegetation, Dow said.

Education was another primary goal, Beckmann said. In addition to the harbor signage, the maps were reproduced on canvas and supplied to Milwaukee Public Schools.

They also hang at Discovery World Science and Technology Museum downtown and are part of the American Geographical Society’s collection at the UWM Libraries.

“Having this tool also helps us understand the impact that our lives have had on life under the water,” Beckmann said. “The environment we accidentally create or the one we harm or restore — all of that impacts what the fish do.”

PUBLIC INPUT SHAPES MAPS

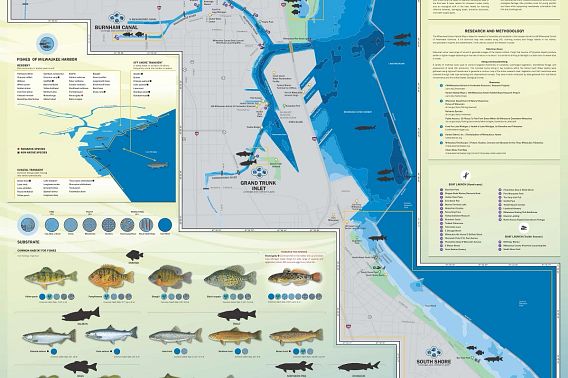

Fifty-one species of fish that inhabit the harbor — and the three rivers connected to it — are represented on five separate maps, along with seven habitat classifications. Beckmann highlighted 16 varieties of fish on the main map with facts like the kind of substrates each prefers, their diets and their habits. The maps include works by nature photographer Jim Edlhuber and illustrations by Stevens Point artist and naturalist Virgil Beck.

“It’s a wonderful marriage of science and art,” Beckmann said.

Deciding what to include was difficult, so she gathered comments on early versions of the maps from the public attending events such as Harborfest, the Wisconsin State Fair and Open Doors Milwaukee.

Viewers usually found a significant place on the map, including fishing spots, that then sparked storytelling about their experiences.

“Stories from the public were really interesting,” Beckmann said. “They would begin by talking about experiences above the water at a particular beach and then progress to talking about fish and life under the water.”

UW-MILWAUKEEA section from one of the new Milwaukee harbor maps shows species and habitat details.

UW-MILWAUKEEA section from one of the new Milwaukee harbor maps shows species and habitat details.BETTER ECOLOGY BOOSTS ECONOMY

The maps and survey data were done in consultation with the Harbor District, Milwaukee Estuary AOC Fish and Wildlife Technical Advisory Committee, and the Army Corps of Engineers, all of which are interested in different aspects of the harbor’s features.

The DNR’s objective is to address area of concern impairments, which will lead to a healthier ecology. And that, Dow said, has the potential to generate an economic return on investment.

Since 2010, funding for the DNR’s remediation projects in the Milwaukee harbor has come largely from the federal Great Lakes Restoration Initiative.

A 2018 study by the University of Michigan showed that between 2010 and 2016, every $1 of spending on GLRI projects produced at least $3.35 in additional economic activity in the Great Lakes region. The model the study’s authors produced could predict similar return on investment through 2036.

Now that the Milwaukee harbor maps are completed, Beckmann has begun working with stakeholders on similar maps for four more harbors along Wisconsin’s Lake Michigan coast — Port Washington, Sheboygan, Two Rivers and Manitowoc.

The maps can offer valuable ecological insights, Beckmann said. “By making this resource available, citizens can be more informed about protecting the environment.”

Laura Otto is a writer for UW-Milwaukee’s Division of University Relations and Communications.

INFORMATION

To access the new Milwaukee harbor maps online, go to uwm.edu/harbormaps. Five maps are available: Milwaukee’s main harbor, Menomonee River and Burnham Canal, Milwaukee and Kinnickinnic rivers, Milwaukee’s outer harbor, and the city’s south shore. You can view the maps, download PDFs or order printed poster copies.

UW-MILWAUKEEBrennan Dow, now with the DNR, has been a key player in research to create maps of fish species and habitat in Milwaukee.

UW-MILWAUKEEBrennan Dow, now with the DNR, has been a key player in research to create maps of fish species and habitat in Milwaukee.RESEARCH LAYS GROUNDWORK FOR FUTURE HABITAT PROJECTS

Elizabeth Hoover

Dotted with industry, Milwaukee’s concrete shoreline appears more hospitable to commercial vessels, pleasure boats and patio dining than to fish and wildlife. But just below the water’s glassy surface, pockets of habitats teem with aquatic life.

“It’s not just urban sheet-pile walls and dredged canals,” said Brennan Dow, the Milwaukee Estuary Area of Concern coordinator at the DNR. “There’s a whole world happening next to you that you don’t know about.”

While a master’s student at UW-Milwaukee’s School of Freshwater Sciences, Dow worked with professor John Janssen on an extensive mapping project to make that underwater world visible. Supported by the Fund for Lake Michigan and the DNR, Dow mapped 42 miles of Milwaukee’s lower estuary, where Lake Michigan meets the city’s waterways.

He spent two years boating up and down the rivers, canals and lakeshore “like a lawnmower,” and he used sonar to collect information on the waterbed’s depth and composition. The information helped him identify likely locations for fish habitats.

Dow then sought out those habitats, donning diving gear and going underwater for a closer look at what lived beneath.

“I found bass, bluegills and other little baby fish,” he said.

These biological hotspots were isolated from each other, limiting their viability. Dow created a massive spreadsheet cataloging each location with suggestions on how to connect and enhance them.

DAN EGANUW-Milwaukee professor John Janssen, left, and Brennan Dow during an outing for their Milwaukee harbor map research.

DAN EGANUW-Milwaukee professor John Janssen, left, and Brennan Dow during an outing for their Milwaukee harbor map research.TURNING VISION INTO REALITY

After wrapping up his research, Dow has begun to put his habitat ideas into practice and has scaled it to address the entire Milwaukee area through his role with the DNR.

Since starting the job in May 2019, Dow has ferried his list of projects — along with those of other researchers and organizations working on water quality and habitat restoration — through a rigorous vetting process. This final list will be provided to the Environmental Protection Agency.

“Milwaukee is never going to be like Door County, with amazing nature and tons of wildlife,” he said. “Instead, we want to get to a place where we have a successful, sustaining population in an urban setting.”

Meanwhile, his technical map has gotten a makeover from Kim Beckmann, associate professor in UWM’s Peck School of the Arts. Beckmann worked with Janssen to translate the data Dow collected into accessible maps and signage for area parks.

“Her work (bridges) the gap between the science and the public,” Dow said of the finished maps.

He looks forward to a time when visitors to the Milwaukee shoreline can see the area as a living, dynamic ecosystem.

“It’s important to show people there is a big push to clean up Milwaukee,” Dow said. “And, yes, there really are fish out there.”

Elizabeth Hoover is a Ph.D. student and teaching assistant in English at UW-Milwaukee.