<i>Cygnus buccinator</i>: A comeback for the ages

RESEARCHERS REWIND 30 YEARS TO TELL THEIR FIRST-PERSON TALE OF SECOND CHANCES FOR AN ESTEEMED SPECIES

Sumner Matteson and Randy Jurewicz

In memory of Rodney J. King, Terry J. Kohler and W.C. "Joe" Johnson

DNR biologist Sumner Matteson collects eggs from a trumpeter swan nest on the remote Minto Flats in Alaska in June 1989.

DNR biologist Sumner Matteson collects eggs from a trumpeter swan nest on the remote Minto Flats in Alaska in June 1989.© RODNEY KING

Thirty years ago, the two of us began a remarkable but uncertain journey. As Department of Natural Resources conservation biologists, we were part of Wisconsin’s trumpeter swan recovery program, launched in the late 1980s to bring back the species long extirpated from the state.

The plan was to collect eggs from the wilds of Alaska to be hatched at the Milwaukee County Zoo. The young would be reared in captivity and in the wild before they were released. DNR research scientists, wildlife managers and technicians were involved along with participants from the zoo, UW-Madison and scores of organizations and individuals.

In spring 1989, three years after the state set a recovery goal of 20 breeding and migratory trumpeter swan pairs by the year 2000, we prepared to go to Fairbanks, Alaska, our launch point west toward the vast wetland complex known as the Minto Flats. This was where the first of our Alaskan trumpeter swan egg collections would occur.

In the two previous years, Wisconsin biologists had attempted to cross-foster trumpeter swan eggs under mute swans in southeastern Wisconsin. Only one cygnet survived to flight stage, largely because of snapping turtle predation — a disappointing and stunning failure.

The late Richard Hunt — a DNR waterfowl research biologist and now Wisconsin Conservation Hall of Fame member — emphatically told us at the time, "I'll never see trumpeters established in the state in my lifetime!"

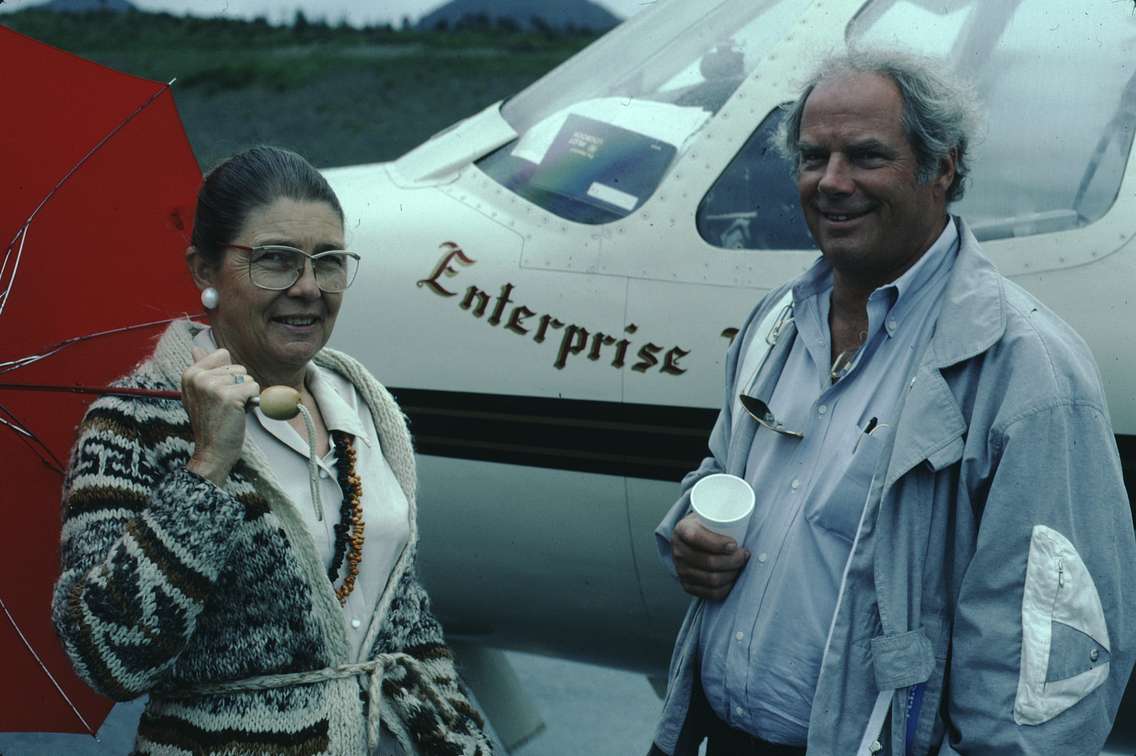

As 1989 approached, Wisconsin was in line to collect trumpeter swan eggs in Alaska, following in the footsteps of the Minnesota DNR's program. We started looking into commercial flights when, much to our surprise, Sumner received a call from Mary Kohler. She had heard from then-Gov. Tommy Thompson that we were exploring the best way to make the round trip to Alaska.

Mary and Terry Kohler donated the use of their private plane and co-piloted it on egg collection trips to Alaska.

Mary and Terry Kohler donated the use of their private plane and co-piloted it on egg collection trips to Alaska. © SUMNER MATTESON

Mary and Sumner had met two years earlier when he helped to lead an International Crane Foundation trip to China. When Sumner told her the plan was to collect swan eggs every year through 1997, Mary enthusiastically broke in with, "We're in! We'll fly you to Alaska and back."

"You mean this year?" Sumner asked.

"No, for the next nine years!" Mary replied.

Thus began the dedication of Mary and her husband, businessman Terry Kohler, to the trumpeter swan recovery program. The Kohlers' commitment, part of several statewide conservation efforts on their part, continued for more than a decade after the egg-collection work ended in 1997.

Anxious about egg collection

Even though the transportation issue was settled, there was considerable trepidation regarding the egg-collection process itself. No Wisconsinite — not even Dick Hunt — had any experience with trumpeter swans in the wild. Sumner's experience was primarily with waterbirds (not waterfowl) and Randy was a mammal guy who had focused largely on timber or gray wolves for much of his career.

Randy asked Sumner to be the egg collector while he focused on how best to keep the collected eggs viable. Fortunately, we had the benefit of learning from the experience of those who preceded us in Alaska — the Minnesota DNR and principally nongame chief Carrol Henderson.

That first year we used three large black-box suitcases equipped with hot-water bottles Carrol had used for keeping trumpeter swan eggs warm when he collected them. Carrol kindly allowed us to borrow these containers for our maiden voyage.

To become familiar with trumpeter swan eggs, we visited the only places known to have breeding trumpeters in Wisconsin — game farms. There we observed the electronic "candling" of swan eggs, looking inside at different points to learn the stages of egg development. We studied whatever manuals we could to help with further pictorial identification of egg development.

In addition to the large black suitcases, Carrol Henderson also provided the same field candler he had used in Alaska at trumpeter nests. Basically, it was a black rubberized coffee can with different-sized holes at either end allowing one to view an egg without unwanted light.

Carrol also provided invaluable counsel regarding how to look at and assess eggs in the wild. If the egg looked opaque, without any embryonic development, it was either recently laid or "bad" (dead or nonviable) and therefore one to be left behind. Bear in mind, we followed strict U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service protocols requiring we leave in the nest at least two viable eggs, or eggs we believed to be fertile based on our field candling.

Eye from 'Sky' on nesting sites

The late Rodney "Sky" King, one of five Fish and Wildlife Service pilot-biologists in Alaska at the time, played an essential role in our egg-collection trips. In previous years he had played a similar role with the Minnesota DNR in locating trumpeter swan nests during May flights, including those he deemed most accessible for visiting during egg collection in early June.

Rod flew us in a float plane to wetland sites he had marked on a series of topographic maps and advised us on how to best approach each nest, especially if a "cob" (male swan) or "pen" (female) was highly defensive. Rod then would return to each nest to monitor productivity and determine how and if egg collecting had affected nesting success.

Trumpeters typically produce clutches ranging in size from five to nine eggs, with smaller clutch sizes often common with younger birds.

"We returned in the fall," Rod later told us, "and it didn't seem to matter whether they would start out with eight or six or four or two eggs. It seemed that the average was about three cygnets they ended up raising."

Into the wild

Along with us on June 5 as we headed for Fairbanks, was the late Joe Johnson, a highly opinionated, chain-smoking, gravel-voiced Michigan waterfowl biologist, who was the leader in bringing trumpeters back to Michigan, and a great resource on waterfowl breeding ecology. He had designed two wooden crates into which would go 20 eggs for Michigan's trumpeter program.

The flight from Milwaukee to Fairbanks took 11 hours, including two stops en route. We arrived at 11:45 p.m., Fairbanks time, to behold the land of the midnight sun. Instead of darkness, the light was subdued.

Rodney "Sky" King (kneeling) piloted the float plane used to spot and gather eggs from the wetland sites. Randy Jurewicz (left) hands off just-collected eggs to Sumner Matteson.

Rodney "Sky" King (kneeling) piloted the float plane used to spot and gather eggs from the wetland sites. Randy Jurewicz (left) hands off just-collected eggs to Sumner Matteson.© MARY KOHLER

The following morning, Rod flew Randy, Sumner and Mary Kohler in a Cessna 187 float plane about 65 kilometers west to the Minto Flats and a remote cabin. Terry Kohler and Joe Johnson came out later in a separate float plane hired by Terry for the occasion.

The Minto Flats is a relatively flat and seemingly endless wetland complex characterized by myriad permanent and semi-permanent lakes surrounded by boreal forest and open meadows mixed with sedges and grasses.

At the cabin, Randy heated water over a stove and prepared hot-water bottles for the Wisconsin and Michigan egg containers. Then we were ready for the flight.

After dropping off Randy and Mary, Rod flew Sumner to the first nest on his topo map, taxiing right up to a nest. The collection itself proved somewhat challenging, made more so by Sumner's battle with severe air sickness brought on by circling over the nesting sites.

In later years, this reaction by Sumner — triggered by an inner-ear condition — thankfully was corrected with a scopolamine ear patch, but that first year was the hardest 13-hour period he'd ever experienced. At one point, Rod turned to Sumner and said, "You're not going to expire on me, are you?"

Sumner had taken to wearing a winter beanie because his condition left him seriously dehydrated and cold, despite a 70-degree day. But he drew on his experience as a teenager on long Arctic canoe trips with his father — and soldiered on to keep the objective of collecting all 60 allotted eggs. In the land of the midnight sun, the team could collect well into the evening.

High degree of difficulty

Reaction by parent birds to nest visits was quite variable, with some leaving the nest and swimming far away. Others, often the cob, stood ground and charged.

"Once the eggs get fairly close to hatching," Rod explained, "the adults are really drawn to protect the nest because then it's only a matter of a few days before they're outta here."

Each egg we collected was given a letter and number penciled in on the topo map to mark the collection location. Then the eggs were placed in a small gray suitcase and moved to the float plane, where they were transferred into one of the larger black suitcases, warmed by the water bottles to temperatures between 92 and 97 degrees Fahrenheit. As each black container was filled, the float plane returned to the cabin base camp where Randy waited to exchange an empty black suitcase for the full one.

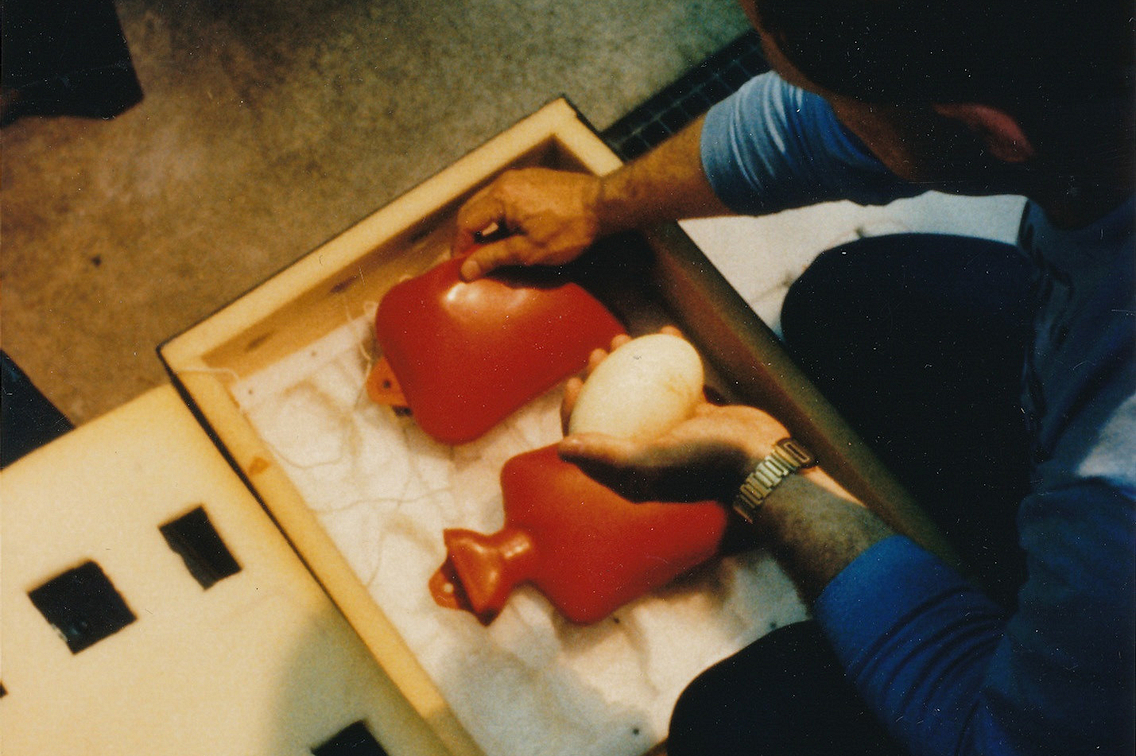

DNR biologist Randy Jurewicz packed trumpeter swan eggs with hot-water bottles to keep them at the right temperature on the trip from Alaska to Wisconsin.

DNR biologist Randy Jurewicz packed trumpeter swan eggs with hot-water bottles to keep them at the right temperature on the trip from Alaska to Wisconsin. © DNR FILES

Later in the egg-collection years, one of Terry Kohler's companies — the Vollrath Co. — developed a mobile, battery-powered incubator with a built-in fan that automatically turned on when the temperature exceeded 97 degrees. But in 1989, it was a different story. It was the job of our water bottles placed directly on the eggs to keep them warm.

What a challenge it was for Randy to monitor the egg temperature inside the egg crates, especially during the trip back to Wisconsin. The temperatures would stay high, high, high — and then suddenly plummet as the water bottles lost their heat.

As Randy later explained to reporters, we started to stage our return trips to airports along the way back based on the water temperatures in airport janitor rooms because we wanted to get the absolute hottest temperatures available.

Hatching, rearing and migration success

The final plane stop was a landing in Milwaukee, where Milwaukee County Zoo staff met us to rush the eggs to the zoo's large, modern incubators. The zoo aviary staff that first year was run by Ed Diebold and later by Kim Smith.

In the wild, hatching success is normally between 60 and 80 percent, but due to the outstanding care by zoo staff, we experienced 95 percent hatching success in 1989, with a subsequent overall average success rate of 93 percent for all years through 1997.

Nineteen of the 20 eggs collected for Michigan in 1989 also hatched successfully, prompting Joe Johnson to joke at a later swan conference: "Sumner Matteson couldn't use the smell test on that bad egg because he was too sick!"

The Wisconsin swan cygnets that hatched that first year were placed into two programs. One was captive-rearing, where wing-clipped cygnets were kept for nearly two years on a fenced pond at the General Electric Medical Systems plant near Pewaukee. Biologist Maureen Gross was in charge of overseeing their care.

Also that first year, several cygnets in the captive-rearing program were placed temporarily at a pond within the Oakhill Correctional Institution in southern Dane County, under the care of wildlife management biologist Ricky Lien. After a short time at Oakhill, those swans were moved to join the others at the G.E. facility in early 1990.

The other program for the cygnets was decoy-rearing, run by UW-Madison wildlife ecology master's student Becky Abel. Decoy-rearing was the brainchild of former UW-Madison wildlife ecology professor Stanley Temple and Abel, along with input from Michael Mossman, then a Wisconsin DNR research ecologist.

Mossman also was charged with selecting lead-free and powerline-free emergent marshes as release sites. These sites had abundant and plentiful foods such as sago pondweed, arrowhead and other aquatic plants.

In the decoy-rearing program, a life-sized decoy was used to imprint cygnets at the Milwaukee County Zoo.

In the decoy-rearing program, a life-sized decoy was used to imprint cygnets at the Milwaukee County Zoo.© ROBERT QUEEN

A life-sized trumpeter decoy was used at an isolated zoo chamber to imprint cygnets right after hatching by Abel and her UW-Madison interns. After about a week, the cygnets were flown to selected wetland sites.

There, in camouflaged float tubes, the interns used a similar trumpeter decoy to lead the cygnets to feeding and loafing sites on the marsh, then back again to temporary pens for the night. They did this until the swans reached fledging age at about 16 weeks, when they were allowed to migrate.

Would the birds migrate that first fall without parent birds to guide them? That was the question uppermost in our minds. It was answered after some delay when they migrated to a site in Texas, about 15 miles north of Dallas.

'So far, so good'

Back to that 1989 egg-collection trip. Perhaps the most memorable moment occurred near the end of the 13-hour expedition. As Rod taxied up to a nest and Sumner was mustering the energy to collect one more egg, the cob was reluctant to move. Finally, he slipped off the nest at the last instant.

If we thought that was that, though, what happened next came as a complete surprise. The bird, after becoming airborne, circled around then attacked the rear of the plane, clipping the communication antenna — thus preventing communication with the Fairbanks airport.

"We've just been attacked by a swan!" Rod exclaimed. Always prepared for emergencies, Rod retrieved a ham radio to call his wife, who relayed our estimated time of arrival to the Fairbanks airport. At 11 p.m., pilot Terry Kohler met the crew for the flight back to Milwaukee.

At the Milwaukee airport the next morning, a media gaggle greeted us before zoo staff whisked us away and Joe Johnson hopped a plane to Michigan with his state's egg bounty. Once at the zoo's aviary, and with all Wisconsin eggs safely placed in incubators, Ed Diebold smiled and uttered what became his standard refrain for the next nine years: "So far, so good!"

An avian ecologist with the Natural Heritage Conservation Program, Sumner Matteson has been with the DNR for 38 years. Randy Jurewicz spent 31 years as a wildlife biologist for the DNR until retiring in 2010.

Partners in success

Trumpeter swans were removed from the Wisconsin Endangered Species List in 2009. Today, based on recent Department of Natural Resources aerial surveys coordinated by the Bureau of Wildlife Management, the number of trumpeter swans in the state has climbed to around 5,000, a gratifying and stunning turnaround.

Thanks are due to scores of public and private major partners that joined the DNR in the trumpeter swan recovery effort.

The number of trumpeter swans in Wisconsin is now around 5,000.

The number of trumpeter swans in Wisconsin is now around 5,000.© LINDA FRESHWATERS ARNDT

- Alexander Foundation Inc.

- Bad River Band of the Lake Superior Chippewa

- BP Naperville Research Center

- Brogan Foundation

- Friends of Crex Meadows

- General Electric Medical Systems

- Glacial Lake Cranberries

- Gottschalk Cranberry Growers

- International Crane Foundation

- Johnson Family Foundation

- Johnson's Wax

- Menasha Corp. Foundation

- Michigan DNR

- Milwaukee County Zoo

- Minnesota DNR

- Natural Resources Foundation of Wisconsin

- Ocean Spray

- Ripples Inc.

- Riverbanks Zoo and Gardens

- Society of Tympanuchus Cupido Pinnatus

- Trumpeter Swan Society

- Three Rivers Park District (formerly Hennepin Parks)

- University of Wisconsin-Madison

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

- Windway Capital Corp.

- Wisconsin Conservation Corps

- Wisconsin Society for Ornithology

- Zoological Society of Milwaukee County