It's what hunters do

SIMPLE GESTURE MEANS 'WELCOME TO THE CLUB'

Story by Brian Wettlaufer and illustrations by Jim McEvoy

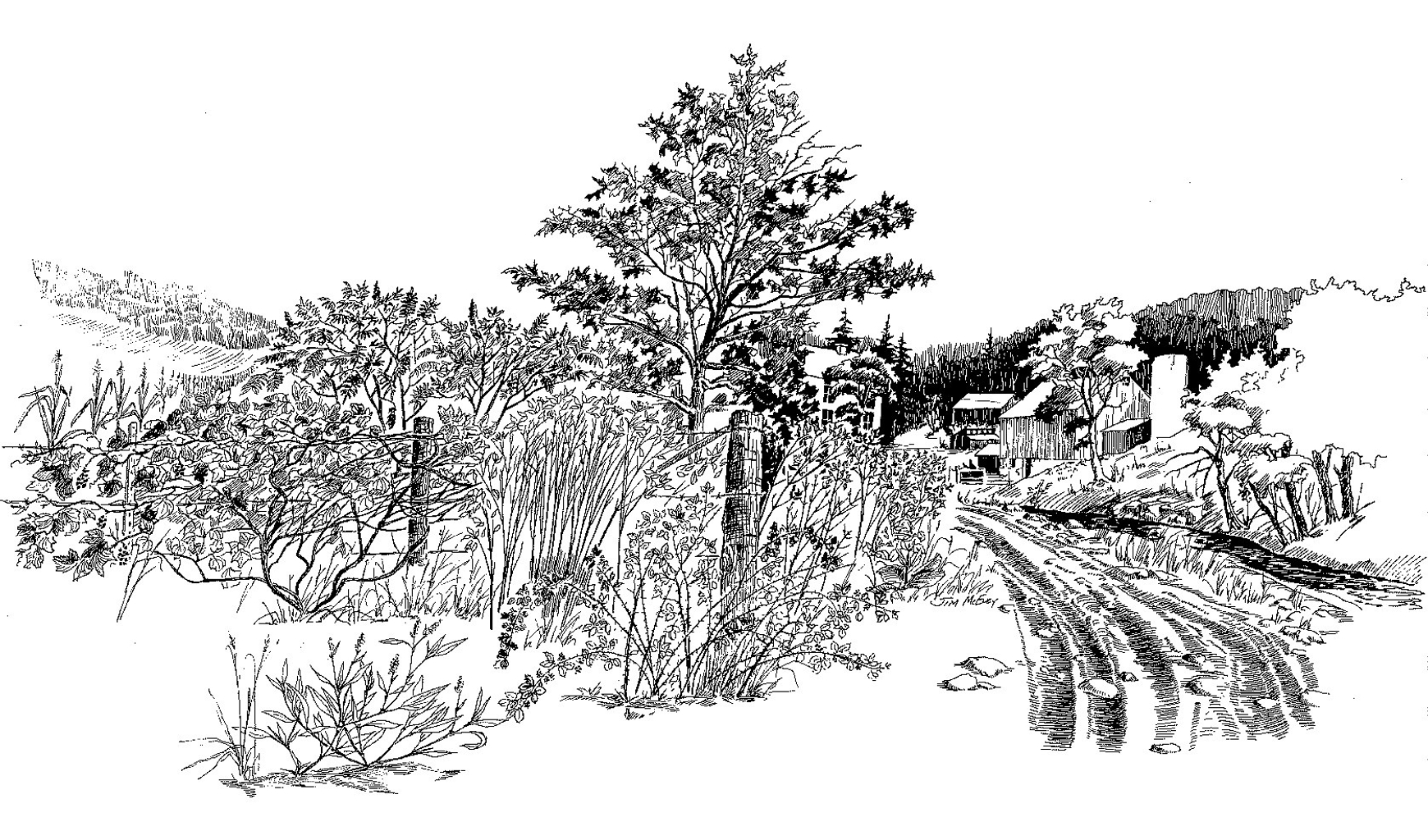

After years of dodging invitations, I reluctantly joined some colleagues on a pheasant hunt in September 2017 at Wild Ridge Game Farm near Watertown. Having little practice with shotguns, my aim that day exposed my inexperience.

But I was not troubled. Hunting was new to me and I didn't expect to bag a bird my first time out. Content just to tag along, I considered the excursion more an enjoyable autumn hike than a test of hunting prowess.

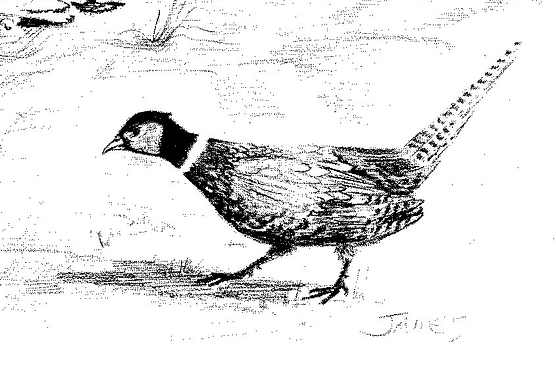

Like all unexpectedly enjoyable adventures, the day vanished too quickly. With senses keen and guns ready, we shouldered our way through harvested corn fields, hiked slippery and mud-rutted tractor tracks, slogged through soggy lowland and huffed up hills that looked deceptively flat from the long gravel driveway.

Outfitted in borrowed orange and armed with my father-in-law's well-worn Remington 12-gauge, I spent more time imitating behavior than looking for prey. Listening to the hunters, I discovered the terms "birdy," "bust" and "lead" referred to, in order: dog behavior, the unintended flushing of birds and a preferred shooting style.

As the day progressed, Jay, the organizer, rotated me with different hunters so I could learn a little from each. I might not get a bird, he explained, but if I observed, tried various shooting techniques and fired some quality shots, perhaps I'd get lucky. Maybe I'd awaken the hunting habit and feel the ancient hunter's twinge with its primal connection of man to land. I had my doubts.

But good hunters are persistent. Not only are they stewards of the land and its bounties but also of their age-old calling. They're also advocates, sometimes not-so-subtle salesmen. Realizing the hunting tradition will continue only with the addition of new members, they bait others with an innocent invitation. And once a newbie is within grasp, they do everything possible to cajole, convince and entice them into the hunting family.

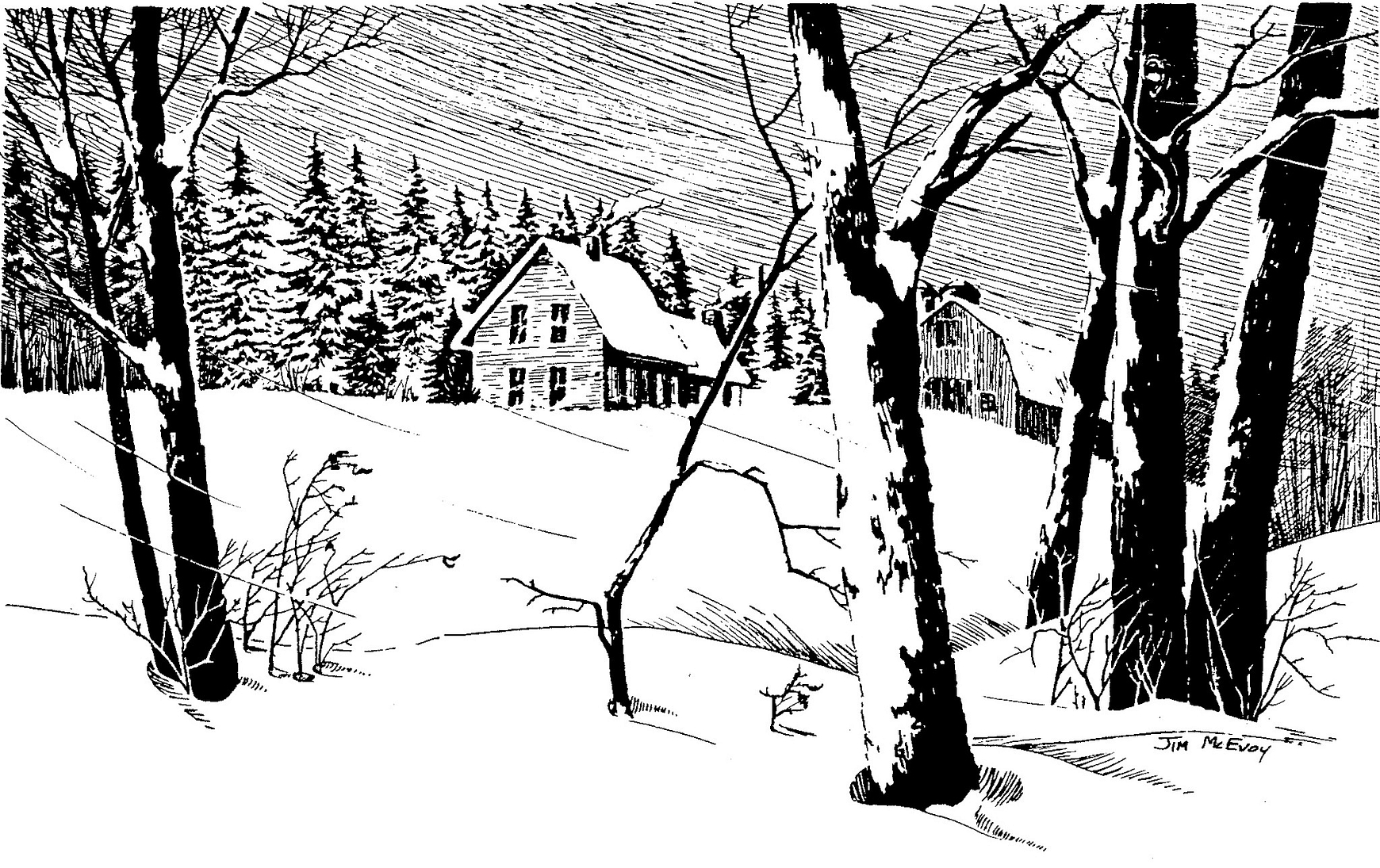

The allure of the hunt often involves nothing more than being content on a quiet stream bank or perched lazily in a creaking tree. Or perhaps it's daydreaming on a stump in a shaded wood, watching over a fertile field where you're invited to deep-breathe the musty, fallow sweetness of land. Those who seek to bring in new hunters convince you there's always hope and promise in the next time, and if next time never comes — well, there was always this time.

First flush of the hunt

At least that's the theory. The reality of my experience was that out of the large collection of ring-necks and chukars released earlier, I'd shot exactly none.

Still, in the dying light as we made a final pass of the fields before turning back to the clubhouse, I was starting to get it. The day's lessons and activities tag-teamed an impression on me and I was at least beginning to think of myself as a hunter, albeit one without a bird.

Now, teamed with Jamie on the left flank, we followed the wet-bottom trough of a hilly field while more experienced hunters Beth and Jay worked the corn patch with their dogs toward others waiting at the far end for the flush. Jamie and I slow-strolled, guns cradled, and chatted in whispers, more interested in the moment than the reason.

Sudden shots chased a single pheasant from the corn, up and almost directly overhead. It flapped and squawked toward a nearby line of pine trees that marked the farm's boundary. Jamie and I raised our guns in tandem and shot, he first, but me so close behind that the crack of fire was almost simultaneous.

His shooting style was measured, seamless, straight — a single, smooth, belly-to-sky motion from rest to shot. Mine was nowhere near so refined — more like an involuntary jerk, a loose, arcing, hope-shot. But the bird fell.

With deference to the newbie

Jamie and I smiled at each other in astonishment and felt the warm adrenaline rise. Beth's dog Piper crashed from the corn, all bark and spittle, eyes afire, fueled by good training and desire to please.

Young Piper emerged from the dark green curtain of trees with the bird in its gentle jaws, the dog did not stop at our feet or even look us in the eye. Never even considering the reward could be ours, it trotted back into the corn. Minutes later the group emerged and the dog owner offered the bird to Jamie and me.

We hesitated. "It's yours," Jamie said.

"No, I'm sure I missed. I think you got it," I replied.

And so the scene was set. While Jamie and I politely dickered and deferred, neither wanting undue credit, the others gathered around, amused at our banter yet knowing the outcome.

Each had lived this moment before, whether over antlers, feathers or fur, in snowy fields or green forests. They knew how the conversation would end.

Only one way decides the outcome — the hunter's way. And those who know it relish it for the life-affirming joy it brings them.

Now it was bringing that same joy to a new member of the club.

Jamie, proclaiming loud and proud that he's shot plenty of birds before, steps aside. I humbly accept the bird. It's what hunters do.

Brian Wettlaufer is a freelance writer in Franklin. Visit his website at BLW Communications.

ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATIONS

For years, drawings by longtime staff artist Jim McEvoy were used to illustrate printed materials at the Department of Natural Resources. McEvoy's beautiful and detailed work captured a huge variety of plant and animal species, landscapes, habitat scenes and more, and his drawings were used for everything from fishing and hunting reports to environmental posters. Wisconsin Natural Resources magazine is fortunate to have several binders full of original illustrations from the now-retired McEvoy. Using a few of these classic black-and-white drawings seemed like the perfect way to add visual interest to two retrospective hunting-related essays, this one and "Buck of a lifetime." Because of McEvoy's decades-long contributions to the agency, it also seemed like just one more great way to celebrate 50 years of DNR.