Buck of a lifetime

MAJESTIC ANIMAL LIVES ON IN LONG-LASTING MEMORIES

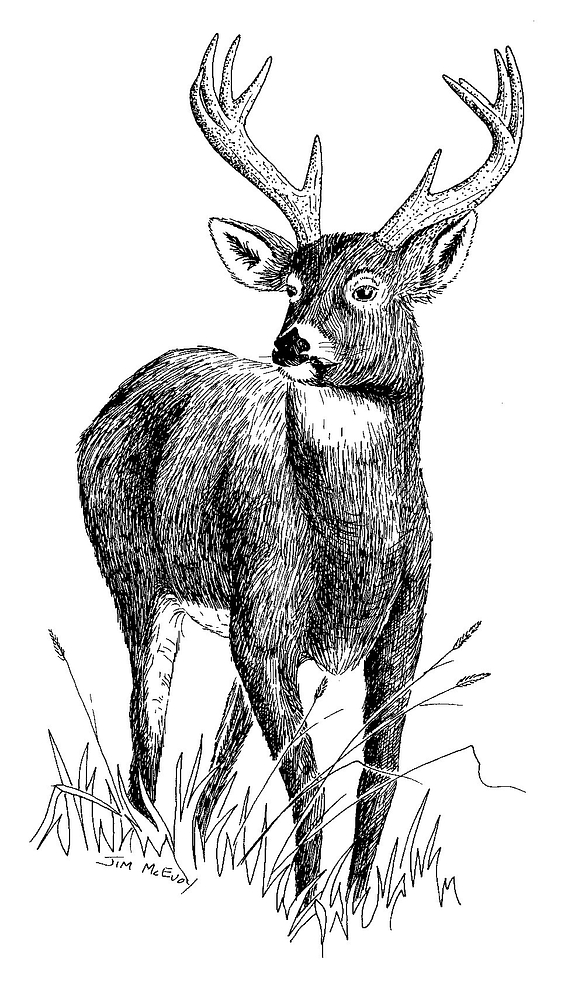

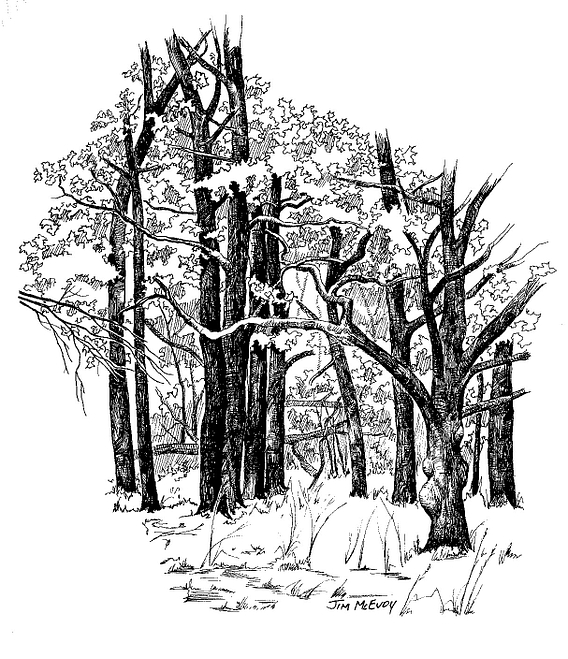

Story by Ron Weber and illustrations by Jim McEvoy

I was 7 years old the first time I ever laid eyes on my buck. He was a 10-pointer with a wide, sweeping rack. The tips curled toward each other in front, leaving a gap of about 6 inches between them.

Each side of the rack was a mirror image of the other with long, thick tines stained dark brown, almost black, from spruce and tamarack pitch. It was a perfect specimen, the most majestic animal I had ever seen, and I wanted one for my own. It would have been inconceivable as a 7-year-old to think I'd have to wait 43 years for the chance to have it.

The buck I dreamed of hung on the wall in my grandparents' guest room above the bed I slept in on our visits there. Each night before the lights were shut off, I would stare up at that buck, the life-like gleam in his eyes hinting that his spirit was still very much alive. In the morning as the daylight slowly brightened the room, I would wait and watch as he materialized out of the darkness.

Even then I was a hunter and dreamed of the day I'd be able to join Grandpa and the others during hunting season and get my buck as Grandpa had done many years before.

A few years later, having missed deer season due to strep throat at age 12, I was looking forward the following season to hunting with Grandpa at last. That October, a month before deer season, Grandpa had spent the day at the hospital visiting Grandma, who was very sick. He returned home for the night, went to sleep and never woke up.

Even at that age, I knew Grandpa was the embodiment of what an ethical sportsman was supposed to be, that how one conducted oneself in the field mattered. I have always wished I could have hunted at least one season with him, but that wasn't where the trail led.

Grandma moved out of the house a couple of years later and my buck went to an out-of-state relative. From then on, it lived only in my memory.

Deer come and go

As I started down my own path as a hunter, I desperately wanted to get my buck. Like most young people, I thought it would come quick and easy. By the time I was in my early 20s, I had learned that though the chance might be there every time out, it was not going to come quick or easy. Also, like many people, I was tempted to try things to better my odds — things that didn't mesh with the ethical values Grandpa and my other hunting mentors had instilled in me.

No, how I got my deer mattered much more than what I got. If I had to bend or break ethical boundaries to get my buck, I'd never be able to look him in the eye the way I had looked at that buck hanging on Grandpa's wall.

It's funny how one year can turn into five and soon a decade. One decade turns into two then three. As the years went by, there were many bucks seen, many shot and many more that slipped away. Though I crossed paths with numerous very nice bucks, none fit the mold of the one that once hung on Grandpa's wall.

More than four decades later, on Nov. 8, 2015, that would finally change.

I had always imagined I'd find the buck I was seeking in some desolate spruce or cedar swamp in the vast Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest, where I had bow hunted and gun hunted most of my life. That's the way it had played out in my fantasy, anyhow. I never anticipated our rendezvous taking place in the broken woods surrounded by farm fields behind my own house in Rusk County.

I have resisted using wildlife cameras, as I still enjoy not knowing exactly what deer are out there and wondering what fate would bring down the trail. As I headed out to sit in my stand that early November afternoon, I had no idea that my buck existed anywhere other than in my mind.

Magnificent as imagined

It had been a warm and windy day with temperatures in the low 50s, and though the rut was in full swing it just didn't seem like November when no gloves and only light clothes were needed. After raking leaves and doing some other end-of-year yard chores, I didn't climb into my ladder stand until around 3 p.m.

I would only have a couple of hours to hunt, but with high deer numbers in the area I was confident I would see deer. By 4 p.m., several deer had come and gone into the corn field about 100 yards south of my stand.

At 4:15, I caught a glimpse of a deer moving toward me through an opening in some balsam firs 80 yards to the north of me. I thought I saw horns, but the deer disappeared into the balsams before I could get a clear look.

A finger of balsams extended through the area where my stand was in a large white pine and it was a natural travel route for any deer heading to the corn field. As I stared into the shadows of the balsams, I could see a deer start to materialize out of the darkness — just like those mornings in bed at my grandparents when my buck would appear.

Suddenly, there he stood, 30 yards away. He was magnificent. It was him, the buck I had waited for my whole life. The sweeping rack, the long dark tines — a perfect 10-pointer. And he was going to walk right past me.

At 10 yards through a light veil of pine branches, I watched him make a scrape and rub his antlers on the branches of a hawthorn tree. He proceeded to walk out in front of me, sniff the ground and stand there seemingly waiting for something.

Two does moving along the edge of the corn field caught his attention and he moved off toward them. I watched as he followed the does and the corn field swallowed him up.

I had never moved, never even considered taking a shot. It was then that I knew.

Five years earlier, I had harvested a small buck with my bow and at that time had pledged to myself that the only deer I had left to shoot was the buck living in the shadows of my memory. But after my buck had come and gone, I realized the truth: I had no more deer left to shoot.

That is a tough thing for someone who has been a hunter since age 7 to admit even to himself, much less to any other hunters who might be reading this.

Two weeks after I saw my buck, on the second day of the gun deer season, my buck of a lifetime became just that for one of my neighbors. I was happy for him and though I had no problem sharing the buck, part of me wished he would have stayed swallowed up by that corn field forever.

Each of us may have a very vivid memory of when our path has crossed with that majestic animal. My neighbor's now hangs on the wall of his den, a beautiful mount, I'm told. My buck of a lifetime hangs where it always has — in my mind's eye. It looks just fine there.

Ron Weber is a DNR forester working out of the Ladysmith Service Center.

ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATIONS

For years, drawings by longtime staff artist Jim McEvoy were used to illustrate printed materials at the Department of Natural Resources. McEvoy's beautiful and detailed work captured a huge variety of plant and animal species, landscapes, habitat scenes and more, and his drawings were used for everything from fishing and hunting reports to environmental posters. Wisconsin Natural Resources magazine is fortunate to have several binders full of original illustrations from the now-retired McEvoy. Using a few of these classic black-and-white drawings seemed like the perfect way to add visual interest to two retrospective hunting-related essays, this one and "It's what hunters do." Because of McEvoy's decades-long contributions to the agency, it also seemed like just one more great way to celebrate 50 years of DNR.