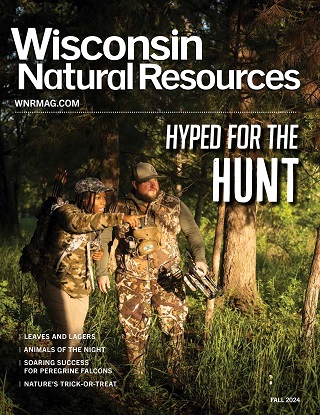

1,000 miles to remember

WISCONSIN HIKER'S NEW BOOK CHRONICLES AMBITIOUS TREK ALONG HER HOME STATE'S ICE AGE NATIONAL SCENIC TRAIL

Jenny Wisniewski

Wisconsin writer and avid hiker Melanie Radzicki McManus has thru-hiked the state's Ice Age National Scenic Trail twice.

Wisconsin writer and avid hiker Melanie Radzicki McManus has thru-hiked the state's Ice Age National Scenic Trail twice.© COURTESY OF MELANIE RADZICKI MCMANUS

When Melanie Radzicki McManus stepped onto the 1,100-mile Ice Age Trail to begin a nearly month-long hike, her biggest fear was an encounter with a black bear. During her 36-day trek she would battle cellulitis in both feet, a knee injury, heat, humidity, rain and poor trail markings — but never a bear.

Perhaps few Americans are aware that Wisconsin is home to the Ice Age National Scenic Trail, let alone nearly 29,000 black bears. In fairness, even many Wisconsinites don't seem to know much about the Ice Age Trail, as McManus discovered during her adventure.

For outdoor enthusiasts like McManus, though, the IAT is a real gem, one of only 11 National Scenic Trails. Managed cooperatively by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, the National Park Service and the Ice Age Trail Alliance, the trail scratches the dirt in not quite half of Wisconsin's 72 counties, winding through thick forests, passing by morasses and over rolling hills, and skirting lakes and streams.

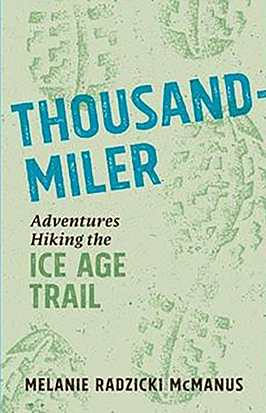

The IAT is a trail McManus loves so much she has trekked it twice — first heading eastward then turning around two years later to walk the same route heading west. It is the first trek McManus chronicles in her book "Thousand-Miler: Adventures Hiking the Ice Age Trail," published in 2017 by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press. "Thousand-miler" is the designation given to those who hike the entire trail, whether all at once via thru-hike, as McManus did, or over time in sections.

Tracing a glacier

McManus, who lives near Madison, began her first Ice Age Trail journey on a hot August day in 2013, though most of her hike would take her into autumn, one of the most beautiful seasons along the trail. Interstate State Park in St. Croix Falls is the trail's western terminus. From there, it meanders two-thirds of the way across the upper section of the state before taking a sharp turn and cutting due south all the way to Green County. It then moves diagonally back up the state to Door County, where it reaches its eastern terminus at Potawatomi State Park.

Envisioned in the 1950s by Raymond T. Zillmer, a Milwaukee lawyer and avid mountaineer, the IAT route is far from random. As McManus observes in her book, Zillmer's plan "traced the edges of North America's last glacial advance into Wisconsin, an inventive route that would allow visitors not only to recreate in the scenic outdoors but also to easily see some of the world's most outstanding glacial features."

The Ice Age Trail, including this stretch at Devil's Lake State Park, is managed jointly by DNR, the National Park Service and the Ice Age Trail Alliance.

The Ice Age Trail, including this stretch at Devil's Lake State Park, is managed jointly by DNR, the National Park Service and the Ice Age Trail Alliance.© JOSEPH WARREN

McManus does a thorough job of explaining the geologic history of the state dating to the trail's namesake Ice Age. The debris that a major sheet of ice left behind when it exited the state for good some 70,000 years ago is significant and the reason for places along the trail with names such as Kettle Moraine and Mondeaux Esker. Both moraine and esker are geologic terms relating to sediment deposited by a melting glacier.

Yesterday's trash is today's treasure along the Ice Age Trail. That's seen in the form of lakes and fertile countryside, waterways, sandstone rock formations in the western section of the state and lots of forestland in the northern third.

People and preparations

In the tradition of Don Quixote, McManus' narrative is episodic, each chapter telling of a new adventure or introducing fellow IAT hikers. She devotes one chapter, "Drew Hendel and Paul Kautz," to a pair also known as "Papa Bear" and "Hiking Dude," two 50-something travelers who had met while hiking the Arizona National Scenic Trail a few years earlier and decided to take their trekking to Wisconsin. "Bob Fay, Archaeologist," "Adam Hinz, Seeker" and "Jenni Heisz, Warrior," are three other IAT hikers Mc- Manus describes in detail.

And she tells of "Jason Dorgan, Speed Demon," a 41-year-old hiker with a big goal — and a tight schedule. "Trying to cover the Ice Age Trail's eleven hundred miles in three weeks was an insane idea," McManus writes of Dorgan's attempt to set a thru-hike speed record for the trail.

Comparisons with Don Quixote are nominal, though, for McManus is no idealist heading into the wilds. She knows the challenges of a major hike. McManus carefully prepared before her journey, beginning with stocking equipment and supplies including nine pairs of running shoes. She also arranged places to stay at night along the way, opting to sleep with friends and family or in hotels and inns rather than to camp as some hikers do.

Next, she set up a crew of people — her husband, sister, parents, daughter and friends — who would shadow her trek, meeting in designated spots to resupply her with water, food, dry socks and shoes. They also shuttled her to the trail in the mornings and to her lodging at night.

McManus knew that like Papa Bear and Hiking Dude, every good hiker, especially a "thousand-miler," needed a trail name. So one of her final preparations was choosing hers: Valderi. The name came from "The Happy Wanderer," a camp song she remembered singing as a child with her family.

Real trailblazers

As she hiked, McManus notes in her book, she recalled Jim Staudacher, the first thru-hiker to complete the IAT in 1979. It was Staudacher who became the first to measure the trail during his thruhike that summer, a year before the trail was officially established in 1980. Working with U.S. Rep. Henry Reuss of Milwaukee, the trail's biggest advocate at the time (with an Ice Age Visitor Center now named for him in Dundee), Staudacher also reported on the condition of each segment of the trail and gave suggestions of where improvements could be made.

A staff member in Reuss' Milwaukee office, Sarah Sykes, was instrumental in helping Staudacher plan and publicize his ambitious first hike, McManus writes. The two met with officials from the Ice Age Park and Trail Foundation (now the Ice Age Trail Alliance), local government agencies, hiking groups and the DNR to go over details of the trek and draw attention to it as a way to promote the fledgling IAT.

Only 22 years old and a student at Marquette University at the time, Staudacher completed his hike in 77 days. He even wrote about it a year later for Wisconsin Natural Resources. "Jim's trip had been exciting, exhilarating, dangerous, tedious and exhausting," McManus writes. "Yet he ended it thrilled and fulfilled beyond measure."

'Singing a siren song'

Hikers often have their unique reasons for an extended trek, and for McManus it was perhaps a tapestry of motivations — her experience as a long-distance runner, her background as a writer, her lifelong residence in Wisconsin — that led her to the Ice Age Trail.

"I could get to know my beloved state on an intimate basis, step by step, in a way few other people ever would, unearthing its hidden secrets, inhaling its heady scents, listening as it spoke to me through the sighing wind, the rustling prairie grasses and the creaking forestland," she explains in her book. "I could become part of the landscape, and the very earth could become part of me.

"As someone who has always felt a primal connection to my home state, the thought was intoxicating. Seductive. The trail was singing a siren song, and I couldn't resist."

McManus experienced many interesting people and places along the trail, but she never stopped for long. Like Jason Dorgan, she had a personal goal to meet. Her spirit of competition led her on a quest to set an FKT — fastest known time — for women.

When she patted the designated rock at the eastern terminus, making the completion of the hike official, McManus had done just that. She completed the 1,100-mile hike in 36 days and five hours, beating the previous record by nearly two weeks.

McManus knew her speed-hike served a purpose — it brought attention to the trail. Though well-loved by many in the region, nationally the trail remains a wellkept secret. With attention comes energy devoted to its upkeep and expansion.

At the time of McManus' hike, the IAT consisted of 650 miles of trail and 450 miles of connecting routes. It continues to be improved by numerous dedicated volunteers across the state and hiked daily by those who enjoy it.

Jenny Wisniewski is a professional writer from Wauwatosa. When not writing, she can be found doing yoga, reading and spending time with her family.

INFORMATION

"Thousand-Miler: Adventures Hiking the Ice Age Trail" by Melanie Radzicki McManus was published in 2017, $20, from the Wisconsin Historical Society Press. For details and ordering information, check Wisconsin Historical Society. McManus continues hiking of all sorts and in June completed a thru-hike of Minnesota's 300-plus-mile Superior Hiking Trail, a trip she chronicled for the Star Tribune newspaper. For more about the author, see her website at Melanie Radzicki McManus. Ice Age Trail information and resources are available from the DNR website; the National Park Service; and the Ice Age Trail Alliance.