SNAPSHOT WISCONSIN JANUARY 2023

You know about the millions of photos collected by Snapshot Wisconsin, but how does this photo data make an impact on the species captured in those photos? Wisconsin DNR research scientists Jen Stenglein and Glenn Stauffer talk about how Snapshot photos of fishers and bobcats have informed important management decisions for the species.

Summer 2022 was a little different for the Snapshot team: an intern joined the team for ten weeks through a program operated by our partner, the Natural Resources Foundation of Wisconsin (NRF). Mira Johnson was able to combine two passions in her work with Snapshot; read on to learn about her research project and two new graphics she created for Snapshot!

Furbearers: The Newest Way Snapshot Is Impacting Wildlife Management

See how Snapshot Wisconsin data has been used to help inform management decisions for Wisconsin’s fishers and bobcats.

A Summer of Science, Art And New Discoveries

A research project, graphic design and even some snorkeling are just a few adventures of Snapshot’s 2022 summer intern. It was an honor to host Mira Johnson from the Diversity in Conservation Internship program!

Furbearers: The Newest Way Snapshot Is Impacting Wildlife Management

The Snapshot team is always looking to expand the ways its data are used for wildlife management. Since its inception, Snapshot Wisconsin has been working towards this goal and has already been incorporated into the decision-making process for several species, such as deer and elk. However, today the Snapshot team shares its newest initiative, informing furbearer management.

Jennifer Stenglein, Quantitative Research Scientist at the Wisconsin DNR and one of the longest-serving Snapshot team members, shares her experience working on this new initiative with colleague Glenn Stauffer, Quantitative Research Scientist for the DNR. Together Stenglein and Stauffer headed up this initiative, with Stauffer in charge of building and running the species models and Stenglein in charge of presenting and discussing the models’ results.

As with most Wisconsin game species, there is a committee that meets each year to set hunting and trapping quotas for furbearers. The Furbearer Advisory Committee (FAC) reviews relevant data and research of each species it oversees and decides what the quotas for the upcoming year should be. There are about 20 species that fall under the category of furbearer, including coyotes, foxes, otters, fishers, beavers, bobcats and weasels. However, much of the meeting focuses on a few select species (bobcats and fishers), since these species have enough data to set annual quotas.

The Initiative’s Origins

The original idea goes all the way back to Snapshot’s first goals. Stenglein explained, “We knew we wanted to use our data to create decision-support products, and the clearest way to do that was to integrate Snapshot data into wildlife species advisory committees.” It took a few years for the project to distribute cameras across the state and collect enough data, but the project is finally reaching the point where it can focus on building these decision-support products and tools. In fact, Snapshot has already found success in incorporating it into the decision-making process for several species. Furbearers were next on the list, according to Stenglein.

Furbearers also made the ideal candidate species to work with next because Stenglein used to be a member of the FAC a couple of years ago. She acted as the FAC’s resident research scientist at that time. Thanks to that opportunity, Stenglein knew how Snapshot data could contribute and integrate into the FAC’s discussions.

“The furbearer program is already pretty data-rich,” said Stenglein. “Each year, [the FAC] has lots of great data coming in, including teeth aging, examinations of carcasses, male/female identifications, harvest information and a bunch of surveys on other metrics. But Snapshot provided a new type of data that the others could not – statewide and year-round data.”

Snapshot cameras collect data at thousands of unique locations across the state, not just at the county or management zone level. The data are also collected year-round, instead of only during hunting/trapping season. Due to these unique qualities, Stenglein and Stauffer had options for how to look at the Snapshot data.

Narrowing Down The Options

According to Stauffer, there are generally two ways of monitoring a population with trail cameras. One way is a simple calculation, the number of photos taken in a given month. Theoretically, areas with higher populations should have more photos than areas with lower populations, so one could use the total photos to monitor the population. No modeling would be required this way. However, Stauffer found that approach to be problematic and overly simplistic.

“The reason I am wary of that method is because of possible differences in detection probability, [or how likely a camera is to detect a given species in a period of time],” said Stauffer. Consider two situations where the number of photos doesn’t accurately reflect the local bobcat population. The first is a camera located in an area with a high bobcat population. However, this camera was set up in a bad location for spotting bobcats, like a field. This camera’s data would lead us to expect few bobcats in the area.

In contrast, a different camera may be in a poor location but have a bobcat camp out in front of it for a few hours. In that period, dozens or even hundreds of photos were taken of a single bobcat. This second camera might lead us to believe there are tons of bobcats nearby. Both conclusions aren’t accurate.

Stauffer prefers the second method, one that factors in detection probability into the model. Stauffer used a fishing analogy to explain detection probability. If an angler or their fishing equipment becomes more efficient over time, then they start to catch more fish using the same effort. The fish population didn’t change, but the angler’s ability to catch a fish increased.

The same is true for trail cameras. If some cameras are better at spotting a bobcat than others (for whatever reason), then that area will record more sightings. Stauffer’s model needed to be sensitive to detection probability, which takes some complicated modeling. Fortunately, Stauffer produces many of the population models used at the DNR and was well-equipped to overcome this challenge.

After incorporating detection probability into the model, Stauffer still had to address situations where animals camped out in front of the camera. He used an analytical method where all photos taken in quick succession counted as a single detection. This way, repeated detections wouldn’t bias the data.

Stauffer also decided to aggregate data at the monthly level to better see population trends and differences in distribution across the state. Looking at data in shorter intervals was problematic since there was too much variation from day to day and week to week. Monthly variation was much more stable and easier to see trends.

What Stenglein And Stauffer Gave The Committee

Finally, it was time to present to the FAC, and the members of the FAC were excited about it. Stenglein said, “The advisory committees are always wanting more information to go off of, so having good, quality data from such a powerful source [trail cameras] was well received.”

The timing was perfect in another way as well because the DNR Office of Applied Science, where Stenglein and Stauffer work out, was in the process of retiring some of their older models and developing replacement ones. The Snapshot data helped maintain high-quality data to inform committee decisions in the meantime.

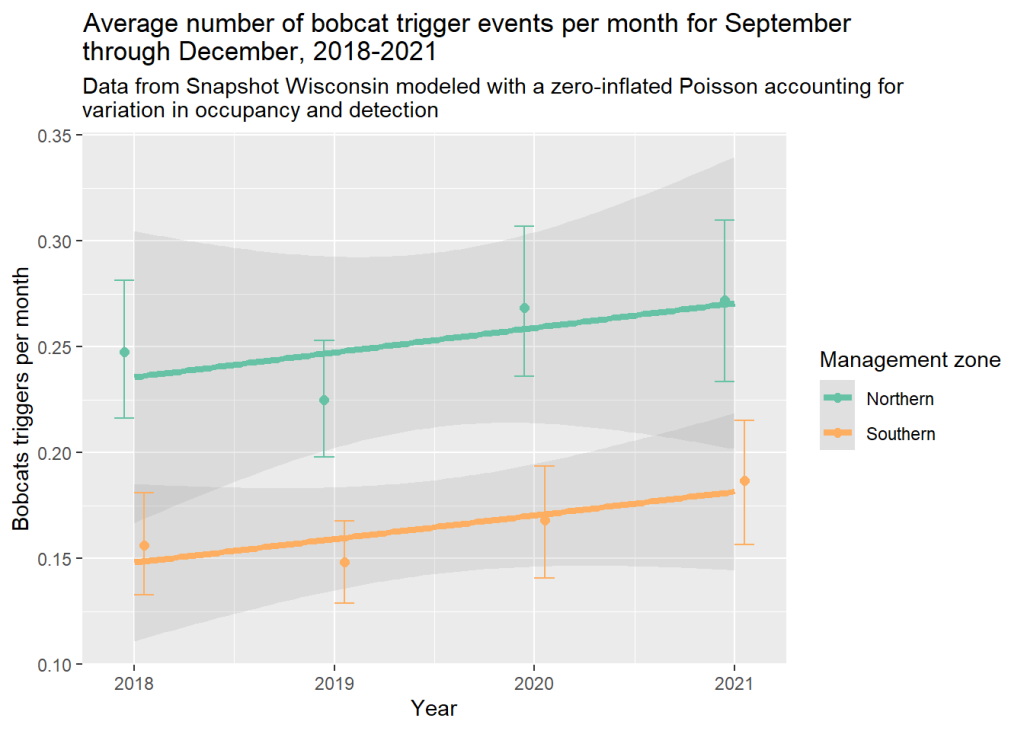

Stenglein gave the FAC a concise report with a few graphs she thought would best inform the decisions they need to make. One graph showed the estimated population size over time (with uncertainty bars on either side in grey). The committee could see from the graph that there’s been no decrease in bobcat detections in recent years, which suggests that the population is stable. Stenglein saw that as a good sign for the bobcat population.

“The committee saw that all the data were showing the same thing - there’s nothing concerning in the data,” said Stenglein. At least for the two species (bobcat and fisher) that Stenglein presented data on, the FAC decided to keep management practices the same as last year. That extra layer of data from Snapshot Wisconsin helped solidify their decision.

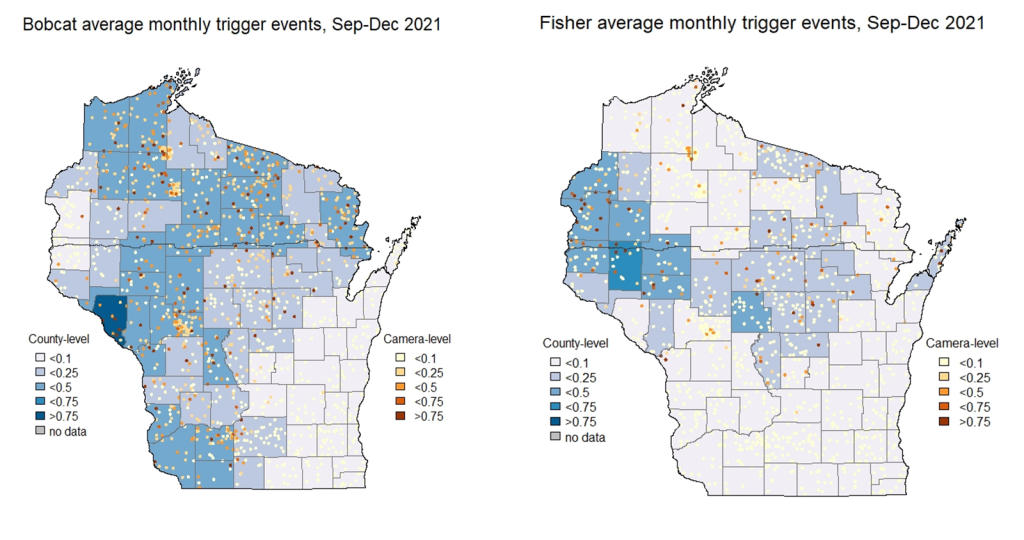

Stenglein also presented a second graph to the FAC. It was a map of Wisconsin with dots and shaded counties. Stenglein said, “Each of the dots represented a different trail camera location, and the darker the dot, the more detections there were each month by that camera. We also aggregated the mean number of trigger events per month at the county level and colored the counties to show relative detection numbers.”

What Is Next?

With their first year under their belt, Stenglein and Stauffer are already thinking about how to improve their support next year. Stenglein mentioned comparing the monthly trigger data to the harvest data. They may want to take a closer look at areas with a lot of trail camera photos but a small predicted population (and vice versa). What do the other data sources have to say about that area? Snapshots could help empower the FAC by offering another way to look at and think about the data.

Stenglein and Stauffer are also interested in looking at how different species interact and shape each other’s distributions across the state. Stauffer pointed to the earlier maps of bobcat and fisher distribution around the state. “It’s interesting that some areas of the state (like the western and central regions) show inverse distributions for bobcat and fisher. The areas with the most fisher detections have fewer bobcat detections and vice versa. [Seeing those kinds of patterns] makes Stenglein and I want to look at multiple species at the same time,” said Stauffer.

Which Species Are Next?

Stauffer said he’s also interested in providing similar data for other species advisory committees. “There are species that have all kinds of distributions across Wisconsin. Some have a statewide distribution but a low density. Other species are abundant in one part of the state and almost nonexistent in others. We’d like to do more modeling on different types of distributions and see what we learn about each,” said Stauffer.

From the modeling perspective, Stauffer wants to know if modeling works better for certain species than others. Is it possible to predict which species modeling will work better? Depending on what they learn, Stauffer also mentioned wanting to look at multi-species models for species like bobcats and fishers with populations that seem interconnected.

As with the furbearer project, the Snapshot team will continue to select future species and products as needed by the agency, but Stauffer was excited at what prospects could be in store. Black bears, opossums, turkeys and skunks are just a few species Stauffer mentioned potentially working with.

Stenglein and Stauffer are busy working on improving their methods for next year. We hope our volunteers are as excited as we are to see what Stenglein and Stauffer can achieve.

Stay tuned to this newsletter for more updates on similar initiatives, as well as other updates from the Snapshot Wisconsin program. You can sign up to receive email updates every time a new newsletter is published.

A Summer of Science, Art And New Discoveries

Snapshot Wisconsin was honored to host an intern from the Natural Resources Foundation of Wisconsin’s (NRF) Diversity in Conservation Internship Program! This ten-week, cohort-based program pairs students interested in natural resource careers with conservation organizations such as the Wisconsin DNR. The goal is to introduce students to the many career pathways in the field of conservation and strengthen their knowledge and skills.

Mira Johnson, one of five NRF interns hosted by the Fish, Wildlife and Parks division of the Wisconsin DNR, chose to spend her summer of 2022 with Snapshot. Now a junior at Lawrence University, Johnson is majoring in biology with a minor in studio art, incorporating two passions into her studies.

From a young age, Johnson knew she wanted to work in conservation. “Growing up I was fortunate to go to schools around the Mississippi River that taught us to appreciate nature,” she said, “I knew from that young age that I wanted to help conserve it in any way possible.” Yearly visits to California beaches with her grandfather sparked a love for marine biology and inspired her to join the Lawrence University Marine Program. There, she conducted her research project on reef-cleaning stations off the coast of Venezuela.

Johnson would explore Wisconsin wildlife and inland fisheries. Johnson joined the Snapshot team in June 2022 and completed her first task: listing goals to accomplish by the end of the internship.

Unique projects sprouted from Johnson’s list. Data wrangling, graphic design and various types of fieldwork would just scratch the surface of Johnson’s activities to achieve her goals. “I gained experience doing daily tasks, such as moderating Zooniverse and preparing equipment for volunteers, but I also got to grow and achieve my own goals by getting to do these projects and participating in fieldwork,” she said.

Communicating Science Through Art

Communicating effectively through design was one of Johnson’s goals. This led to the first of her unique projects: creating new graphics to be used in Snapshot communications. Johnson was excited to show her artistic skills, but first, she needed to do some research. What should go in a design to represent Snapshot? What animals did people prefer to see?

She went right to work reading up on the Snapshot program and its goals, and then used a word cloud developed by the Snapshot volunteer coordinators of animal species volunteers who liked to see the most to decide on which animals to use in the designs. Johnson was particular about choosing an art style she thought volunteers would like. She created seven designs and presented them to the Snapshot team, which voted on the top three designs. “We later narrowed it down to two designs that I then revised,” said Johnson.

The two designs that were cut, “Three Little Bears” and “Elk Crossing” (see below), were inspired by actual Snapshot trail camera photos. Both designs are now available on various types of Snapshot gear. “It’s exciting that I’m coming away from this internship with something that is going to remain with the Snapshot program. I’m glad I get to leave something behind,” Johnson said.

Johnson’s designs titled “Three Little Bears” and “Elk Crossing” will be used on Snapshot gear.

A Scientific Summer

The Snapshot Wisconsin database helped fulfill Johnson’s science-oriented goal: learning about data science. Data science is a complex field that, in short, uses scientific methods, processes, algorithms and systems to extract valuable information from large sets of data (like Snapshot). These valuable insights can then be used in decision-making and strategic planning.

“Data science is an important aspect in all areas of science,” Johnson said, “so that [goal] later became my project of creating a poster on deer rutting behavior where I got to wrangle data from the Snapshot Wisconsin database.”

Johnson tested to see if the timing of the deer rut varied across years by looking at the rutting season from years 2019-2021. From this, she can begin to evaluate what factors may cause the rut to change or stay the same from year to year. She worked with Ryan Bemowski, Snapshot Data Scientist and Engineer, to dive into the massive Snapshot photo database and round up the proper data. Together, they looked at Snapshot trail camera photos of antlered and antlerless deer and then created a graph that looks at years and antlered deer.

Johnson had to think not only about what kind of data she would need to lasso but how to get data and clean the data. The project gave her a new perspective on using data in research, especially when starting a project from scratch. “It was a valuable experience to see all the steps that go into designing a research project that I was previously unaware of. I received a lot of support and guidance from a research and data scientist who made what at first seemed like a daunting project achievable,” Johnson said.

This project will continue even after her internship ended August 19. She is currently working on the

analysis of the data she rounded up. After her analysis, she will present the data in a poster at the Wildlife Society Conference in Spring 2023.

Into The Field

During her internship, Johnson also had the opportunity to travel in the field and shadow various staff members across the Wisconsin DNR’s Office of Applied Science (OAS). She searched for elk calves to collar, joined fish research crews for electrofishing and creel surveys, banded urban-dwelling ducks around Madison and snorkeled to photograph fish habitats.

“I really like that I got to be hands-on for some of these trips,” said Johnson. She mentioned the duck banding trip and how she was able to help catch and hold the ducks for banding as one of her favorite hands-on experiences.

Johnson was also able to use her artistic side in fieldwork. Photos were needed for a research project studying the effects of downed trees along shorelines on local fish communities. Four years ago, various trees were cut along the shorelines of Sanford Lake and allowed to fall into the water. Over time, DNR fisheries research scientists observed the changes in the environment and fish community. Now, those changes needed to be documented using photography.

Johnson joined OAS Communications Specialist Rachel Fancsali for the underwater photoshoot, helping photograph the shoreline above and below the water. She used snorkeling gear to get close enough to the fish hiding in the safety of the downed trees and stay underwater long enough to snap a photo. “It was a challenge trying to get close-up shots of the fish without spooking them,” said Johnson. With some patience, eventually, a few panfish were curious enough to investigate (see below).

Discovering A New Path

Before she knew it, Johnson’s summer with Snapshot was over. “I was able to accomplish a lot more than I expected,” Johnson said, “and I had a lot of fun. This internship was just so different than what I imagined internships to be.”

Johnson knows she wants to continue biology research and pursue her love of marine biology. But some of her experiences over the summer revealed a new career path she wants to consider: science communications. “It has always been a dream to be able to combine my interests in art and sciences, but I didn’t know there was a career for that,” Johnson said. “Finding that there is a place for science and art to come together was something I don’t think I would have heard about unless I did this internship.”

Johnson returned to Lawrence University for her junior year in the fall and is looking forward to continuing her studies. The Snapshot team would like to thank her for all her hard work this past summer and good luck in her future!

To learn more about the Natural Resources Foundation of Wisconsin’s Diversity in Conservation Internship Program visit their site here. Applications for the Summer 2023 Diversity in Conservation Internship are now open and the deadline to apply is Friday, February 24.